Continuing the previous Detailed Explanation of Domain Name Resolution System - Basics, DNSSEC is a set of solutions that make Domain Name Resolution System (DNS) more secure . In 1993, the IETF launched a public discussion on how to make the DNS more trustworthy, culminating in an extension to DNS, DNSSEC, which was officially released in 2005. However, implementing DNSSEC in practice is a very difficult task, and this article will discuss some of the insecurities that exist in the existing DNS system and how DNSSEC addresses them.

Problems with Traditional DNS

From the previous article it is known that when you visit a website, such as www.example.com, the browser sends A DNS message is queried to a DNS cache server. Due to the huge size of the DNS system, it needs to go through several layers of DNS cache servers. To access this website correctly, all cache servers need to respond correctly.

DNS Man-In-The-Middle (MITM) Attack

The DNS query is transmitted in clear text, which means that the middleman can change it during the transmission process, or even automatically determine different domain names and then do special processing. Even using other DNS cache servers, such as Google’s 8.8.8.8, the man-in-the-middle can directly intercept IP packets to forge the response content. Since my country is facing this problem, I can easily show you what happens after a man-in-the-middle attack:

1 | $ dig +short @4.0.0.0 facebook.com |

Sending a DNS request to an IP address that does not point to any server: 4.0.0.0 should get no response. But it actually returns a result in the country I’m in, and it’s clear that the packet was “manipulated” in transit. So if there is no man-in-the-middle attack, the effect is like this:

1 | $ dig +short @4.0.0.0 facebook.com |

The DNS system is so fragile. Like any other Internet service, network service providers, router administrators, etc. can act as “middlemen” to collect and even replace and modify the data packets transmitted between the client and the server. As a result, the client gets incorrect information. However, through certain encryption methods, the middleman can be prevented from seeing the data content transmitted on the Internet, or it can be known whether the original data has been modified by the middleman.

Start With Cryptography

When it comes to DNSSEC, we have to talk about some knowledge of cryptography. Here we start with the most basic cryptography. Cryptography is mainly divided into three categories, and here are the commonly used encryption algorithms for each column:

Symmetric Cryptography: AES, DES

Public Key Cryptography: RSA, ECC

Data integrity algorithm: SHA, MD5

In DNSSEC, two types of cryptography, public key cryptography and data integrity algorithms, are mainly used.

Public Key Cryptography for Digital Signature

Public key cryptography is mainly distinguished from symmetric cryptography: symmetric cryptography uses the same key for encryption and decryption; while public key cryptography uses an encryption key called a public key and a decryption key called a private key—the two keys are relatively independent , cannot replace the location of the other party, and knowing the public key cannot deduce the private key. Both cryptography must be reversible (so the decryption algorithm can be seen as the inverse of the encryption algorithm). Expressed in the form of a function as follows:

Symmetric Cipher

ciphertext = encryption algorithm(key, original)

original text = decryption algorithm(key, ciphertext)

Public Key Cryptography

Ciphertext = encryption algorithm (public key, original text)

original text = decryption algorithm (private key, ciphertext)

Of course, if the private key acts as the public key and the public key acts as the private key, then this is it:

Ciphertext = encryption algorithm (private key, original)

original text = decryption algorithm (public key, ciphertext)

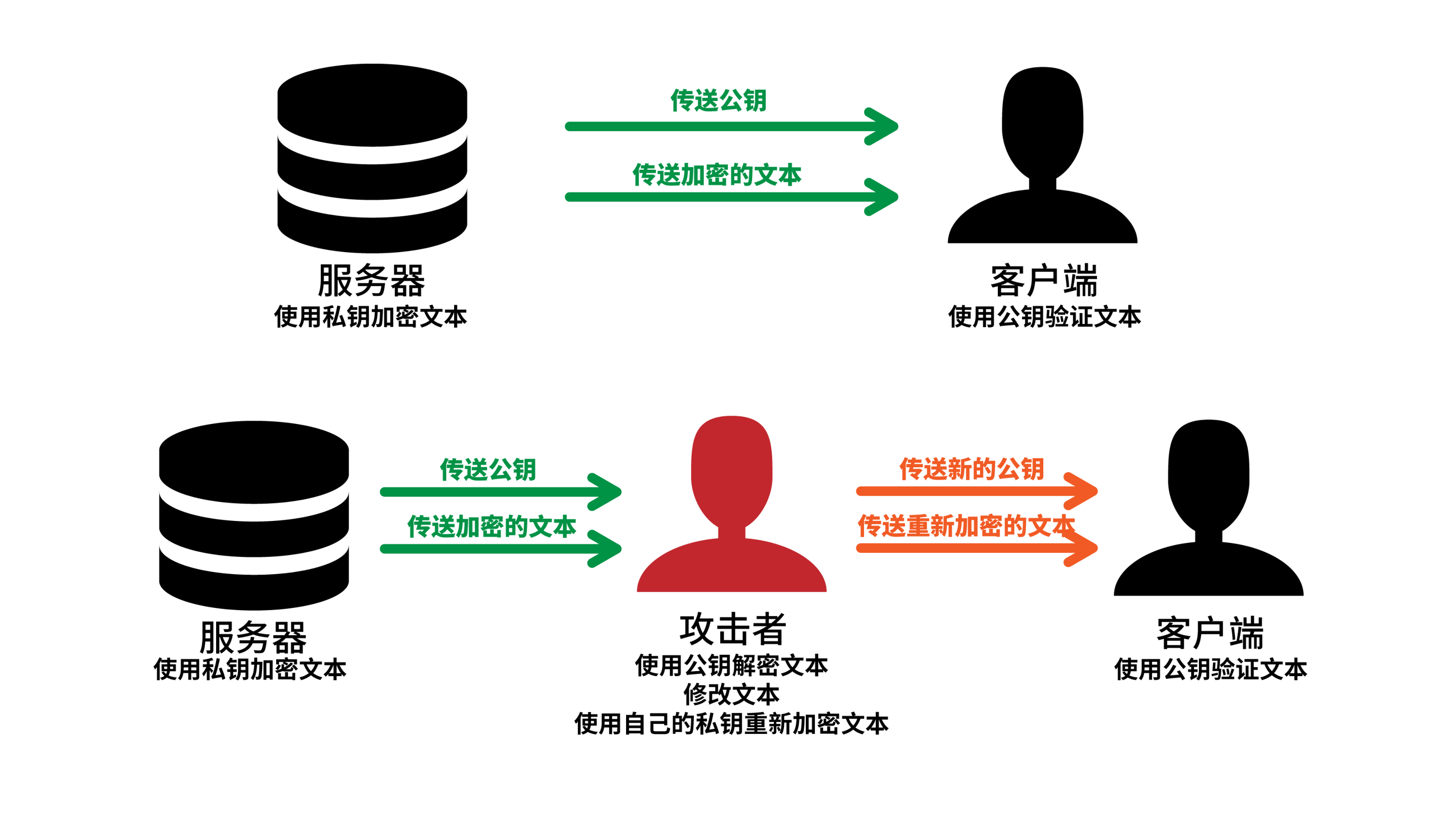

If the server wants to send a message to the client, the server has the private key and the client has the public key. The server encrypts the text using the private key and transmits it to the client, which decrypts it using the public key. Since only the server has the private key, only the server can encrypt the text, so the encrypted text can authenticate who sent it and ensure the integrity of the data, so encryption is equivalent to adding a _ number to the record sign_. But it should be noted that since the public key is public, the data just cannot be tampered with, but can be monitored. If the server here acts as a DNS server, it can bring this feature to the DNS service, but a problem arises, how to transmit the public key? If the public key is transmitted in plaintext, the attacker can directly replace the public key with his own, and then tamper with the data.

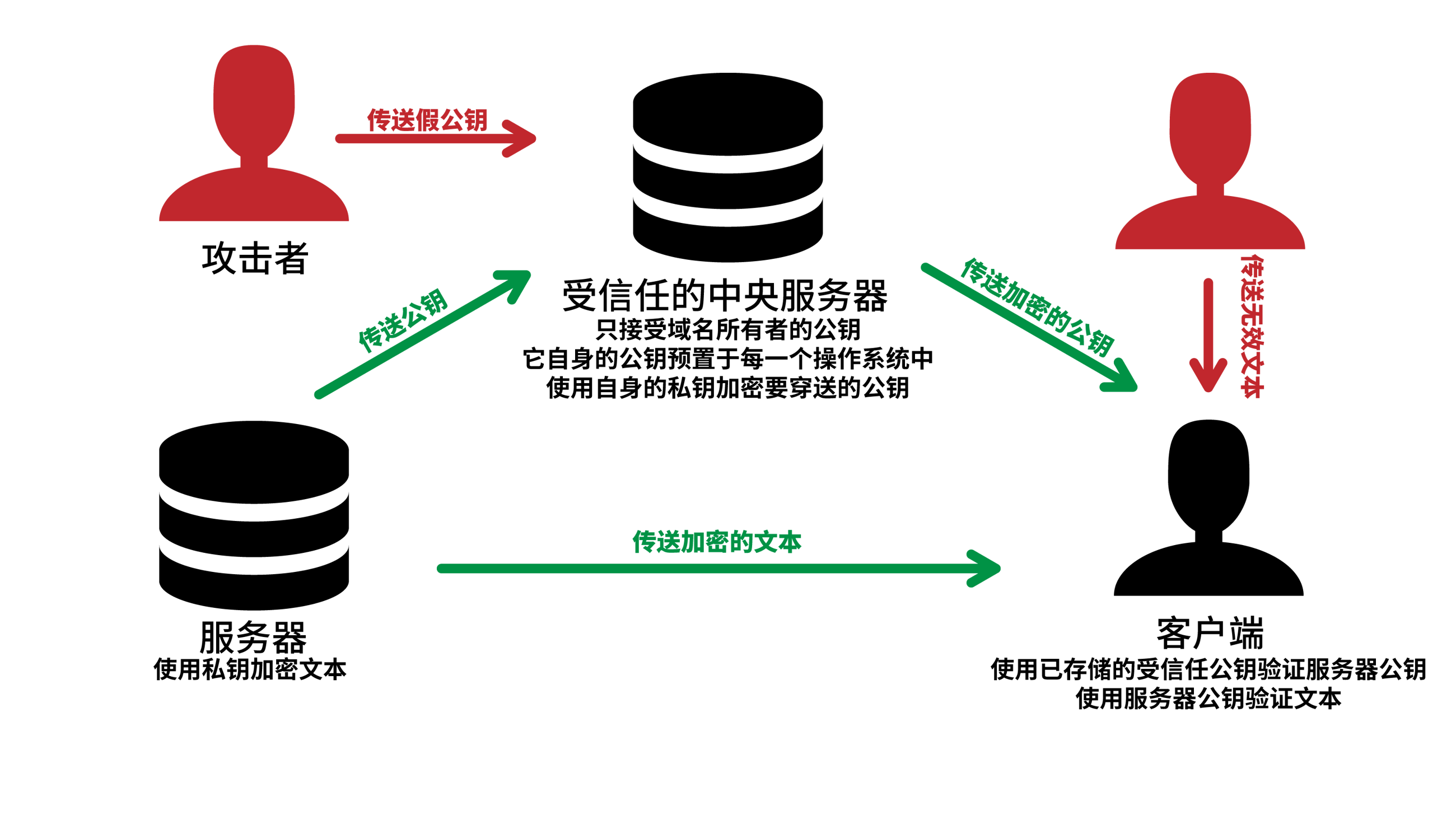

Therefore, a solution is to use a recognized public key server, and the client’s operating system stores the public key of the public key server itself locally. When communicating with the server, the client communicates from this recognized public key server, the user uses the public key built into the operating system to decrypt the public key of the server, and then communicates with the server.

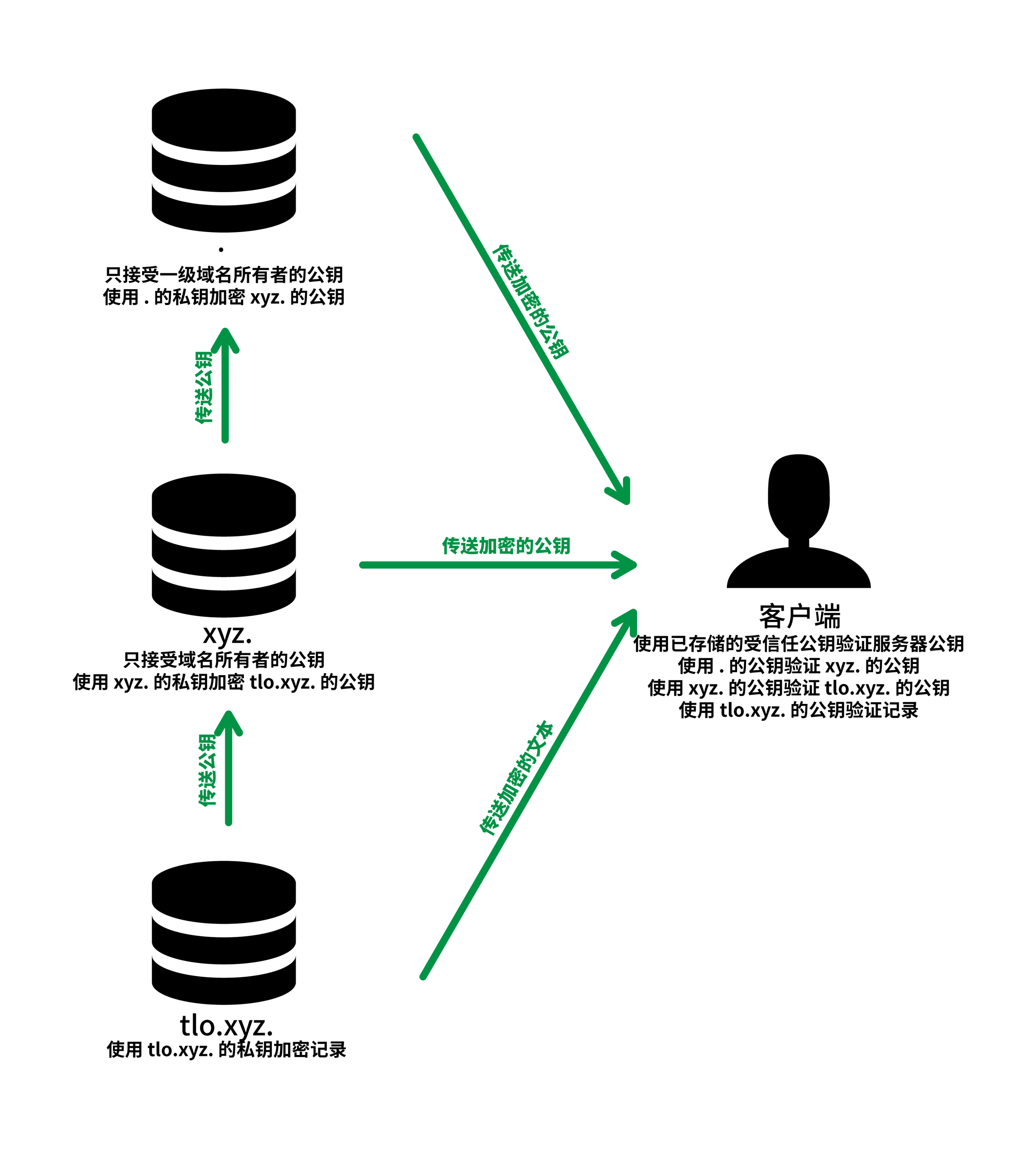

However, DNS is a huge system in which the root name server acts as a recognized public key server, and each of the first-level name servers is also a sub-key server. The last picture is the basic prototype of DNSSEC.

In cryptography, there is also an algorithm for checking the integrity of data. Its “encryption” does not require a key, the ciphertext is irreversible (or difficult to invert), and the ciphertext does not have a one-to-one correspondence with the original text. Moreover, the ciphertext calculated by this algorithm is usually a fixed-length content. The ciphertext calculated by this algorithm is called a hash value. Its characteristics used in DNSSEC are: once the original text is modified, the ciphertext will change. A very important problem with public key cryptography: the speed of encryption and decryption is too slow compared to symmetric encryption. So to improve performance, you need to shorten the text that needs to be encrypted and decrypted. If only the hash value of the text is encrypted, the encryption speed can be greatly improved due to the reduction of the length. When the server transmits, the plaintext text and the hash value of the text encrypted with the private key are transmitted at the same time; the client only needs to calculate the hash value of the received plaintext text, and then decrypt the ciphertext with the public key to verify the two values. Whether it is equal, it can still prevent tampering. This approach is used in DNSSEC, both for encryption of keys and records.

DNSSEC

DNSSEC is an extension that adds verification information to DNS records, so that software on cache servers and clients can verify the obtained data and conclude that the DNS result is true or false. As mentioned in the previous article, DNS resolution starts from the root domain name server and goes down one level at a time, which is exactly the same as the chain of trust in DNSSEC. Therefore, the deployment of DNSSEC must also start from the root name server. This article also starts with the root domain name server.

Differences with HTTPS

DNSSEC and HTTPS are two completely different things, but here is just a comparison of their encryption methods. That is, the encryption method of DNSSEC is compared with TLS.

Differences in Trust Chain Mechanism

When configuring DNSSEC, if you compare it with HTTPS, you can see that the certificate and private key are all directly generated on your own server, which means that this is “self-signed” and does not require any “root certificate issuance”. business”. The owner of the second-level domain name submits the hash value of his public key to the first-level domain name registrar, and then the first-level domain name registrar will sign your hash value, which can also form a chain of trust, which is far better than HTTPS. The chain of trust is simple, and the operating system no longer needs to have so many CA certificates built-in, and only needs a DS record of the root domain name. Personally think that this is a more advanced mode, but it requires the client to parse it step by step, so it is affected by the speed; HTTPS directly returns the entire certificate chain from a server to connect with the server HTTPS only need to communicate with one server. However, DNS records can be cached, so DNSSEC latency can be reduced to a certain extent.

Only Sign, Not Encrypt

The request you send to the DNS server is in plaintext, and the request returned by the DNS server is in plaintext with a signature. In this way, DNSSEC only ensures that DNS cannot be tampered with, but can be monitored, so DNS is not suitable for transmitting sensitive information, but the actual DNS records are almost not sensitive information. HTTPS will simultaneously sign and encrypt in both directions, so that sensitive information can be transmitted. DNSSEC’s signature only, not encryption is mainly because DNSSEC is a subset of DNS and uses the same port, so it is made to be compatible with DNS, and DNS does not require the client to establish a connection with the server, only the client The client sends a request to the server, and the server returns the result to the client. Therefore, DNS can be transmitted by UDP without TCP handshake, and the speed is very fast. HTTPS is not a subset of HTTP, so it uses another port. In order to do encryption, you need to negotiate a key with the browser first. There are several handshakes between them, and the delay also goes up.

Where to Verify?

All of the cases just described are in the absence of a DNS cache server. What if there is a DNS cache server? In fact, some DNS cache servers already perform DNSSEC validation, even if the client does not support it. If the verification fails on the cache server, the parsing result will not be returned directly. Do DNSSEC validation on cache servers with little added latency. But there is also a problem, what if the line between the cache server and the client is not secure? So the safest way is to do an authentication on the client side as well, but this adds latency.

DNSSEC Timeliness and Caching

One of the features of DNSSEC compared to HTTPS is that DNSSEC can be cached, and even if it is cached, the authenticity of the information can be verified, and no middleman can tamper with it. However, since it can be cached, a cache duration should be specified, and this duration cannot be tampered with. The signature is time-sensitive, so that the client can know that it has obtained the latest record, not the previous record. If there is no timeliness, the IP that your domain name resolves to is changed from A to B, and anyone can easily get A’s signature before the change. The attacker can save the signature of A. When you change the IP, the attacker can continue to tamper with the IP of the response to A, and continue to use the original signature of A, and the client will not notice it, which is not expected. However, in the actual RRSIG signature, it will contain a timestamp (not a UNIX timestamp, but an easy-to-read timestamp), such as 20170215044626, which represents UTC 2017-02-15 04:46:26, this timestamp Refers to the expiration time of this record, which means that after this time, the signature is invalid. The timestamp is added to the encrypted content to participate in the calculation of the signature, so that an attacker cannot change the timestamp. Due to the existence of timestamps, there is a limit to how long a DNS response can be cached (the duration is the invalidation timestamp minus the current timestamp). However, before DNSSEC, the control cache duration was determined by TTL, so to ensure compatibility, the two durations should be exactly the same. By doing this, it can be compatible with the existing DNS protocol, can ensure security, and can also use cache resources to speed up client requests, which is a perfect solution.

The Deployment of DNSSEC

In fact, even if you don’t understand or understand the above content at all, it will not affect your deployment of DNSSEC, but you should treat it very carefully. A little carelessness may cause users to be unable to resolve the situation.

Deploy DNSSEC using Managed DNS

Since third-party DNS is used, deploying DNSSEC requires third-party support. Common third-party DNS supporting DNSSEC are Cloudflare, Rage4, Google Cloud DNS (application required), DynDNS, etc. Before enabling DNSSEC, you first need to activate DNSSEC on the third-party service, so that the third-party DNS will return records about DNSSEC. After activating DNSSEC on the third-party DNS, the third-party will give you a DS record, which looks like this:

1 | tlo.xyz.3600 IN DS 2371 13 2 913f95fd6716594b19e68352d6a76002fdfa595bb6df5caae7e671ee028ef346 |

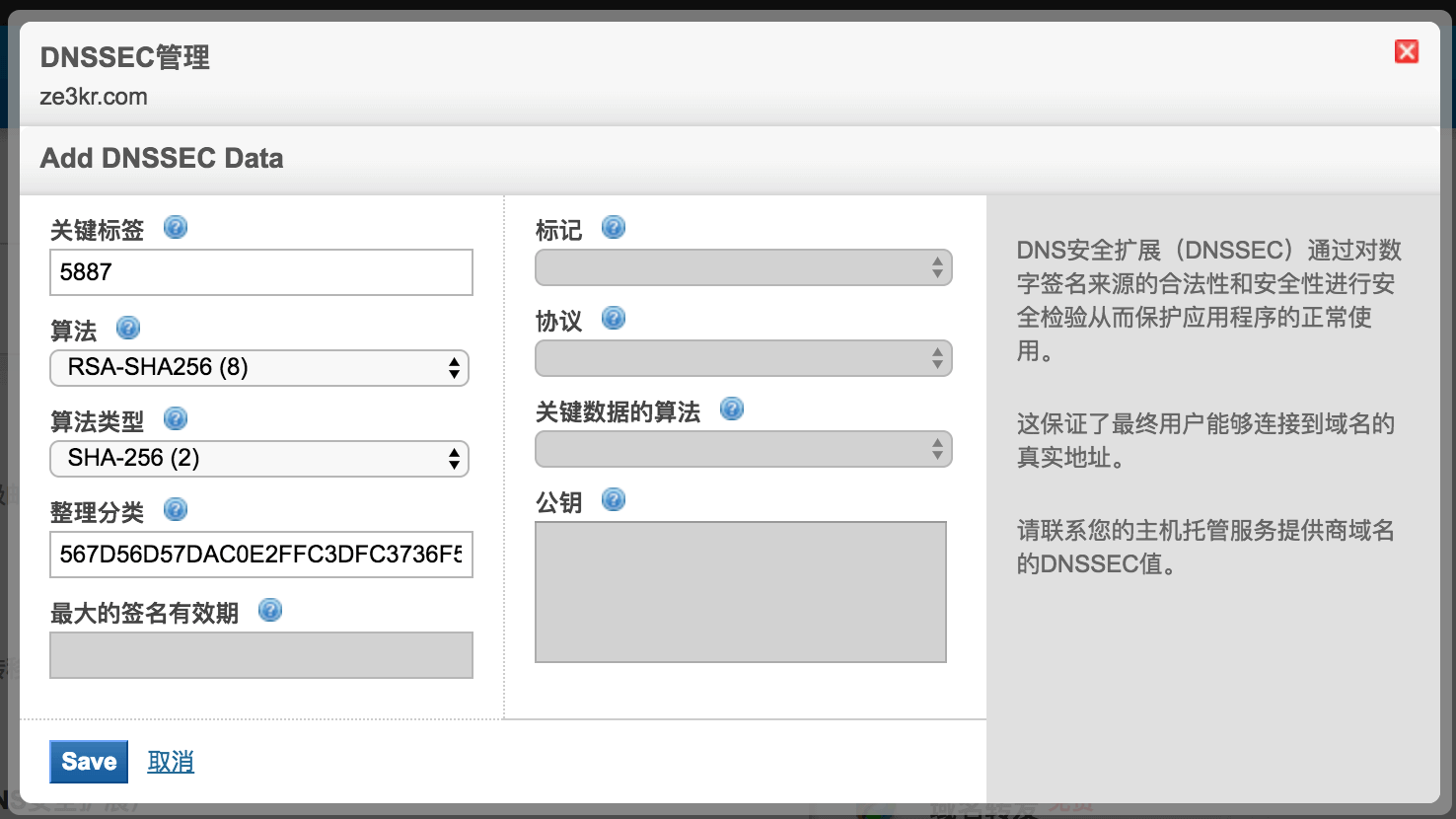

At this point, you need to go to the domain name registrar and provide this DS record for your domain name (some domain name registrars may not support adding DS records, you can consider transferring to [domain name registrar on this site](https:/ /domain.tloxygen.com) or other registrars that support DS records. In addition, some domain name suffixes do not support adding DS records. It is recommended that you use mainstream suffixes, such as .com, etc. Here, the domain name registrar of this site is used as example):

Add and save and everything is OK. Note that Key Tag is the first item in the DS record (corresponding to 2371 here), Algorithm is the second item (corresponding to 13 here), and Digest Type is the third item Item (corresponding to 2 here), Digest is the last item. The rest of the content does not need to be filled out. Some third-party DNS (such as Rage4) will give you multiple DS records at once (same key label but different algorithm and algorithm type), but you don’t need to fill in them all. I recommend only filling in DS using Algorithm 13 with Type 2 or Algorithm 8 with Type 2. These two are the parameters recommended by Cloudflare and the parameters currently used by the root domain name. Filling in multiple DS records won’t give you much security, but may increase the computational load on the client side.

Deploy DNSSEC with Self-Built DNS

To use self-built DNS, you first need to generate a pair of key pairs, and then add them to the DNS service. I have introduced How to add DNSSEC on PowerDNS. After this, you need to generate DS records, usually you generate a lot of DS records, as with third-party DNS, I recommend only submitting DSs using Algorithm 13 and Type 2 or Algorithm 8 Type and Type 2 to the domain registrar.